Fenchel-Rockafellar duality theorem, one ring to rule'em all! - Part 2

I – Introduction

In part 1, we ended with a proclamation of the mights of the the Fenchel Rockafellar Duality Theorem (FRDT). We also showed how classical duality in conic and linear programming are special instances of this more general result. At the moment, we still lack technical material to embark on a head-on proof of the FRDT. The aim of this post is to state and proof the Hahn-Banach separation theorem, an essential ingredient in the “book proof” of FRDT. Of course, in the tradition of the previous post, lots of relevant exercises will be provided with hints on how to solve them. A single subsequent post should then be enough to finally proof FRDT.

|

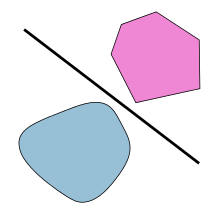

Fig. 1. Showing two disjoint convex sets. The Hahn-Banach theorem predicts the existence of a hyperplane (shown here in black) separating the two sets. In general, the separation will not be as “strict” as shown in this figure. Photocredit: www.wikipedia.org

Why are we here ? Why are we talking about separation theorems ? Remember that FRDT is concerned with the problem

\[p = \inf_{x \in \X} f(Ax) + g(x),\] \[d = \sup_{\ystar \in \Ystar}-f(-\ystar)-g(\Astar\ystar),\]where $A:\X \rightarrow \Y$ is a bounded linear operator between normed vector spaces, and $g:\X \rightarrow (-\infty, +\infty]$ and $f:\Y \rightarrow (-\infty, +\infty]$ are functions (convex or not!). It was shown that weak duality holds: $p \ge d$. To get strong duality (i.e $p=d$), we’ll be led (next post!) to admit the subdifferential inclusion “$ \partial (f\circ g)(x) \subseteq \Astar\partial f(Ax) + \partial g(x)\;\forall x$” (the reverse inclusion is unconditional!), which holds under certain delicate conditions on $f$ and $g$: it’s sufficient for $f$ and $g$ to be proper convex lower-semicontinuous and for there to exist a point $x_0$ interior to $\dom(g)$ such that $f$ is continuous at the point $Ax_0$. This sufficiency will be established by means of the geometric version of the Hahn-Banach Theorem (the so called Hahn-Banach Separation Theorem), which is the main objective of the current post.

I.1 – Recap of part 1

In part 1, we developed a very basic “functional analysis” (linear functionals, continuity, topological dual). Notions like cones, dual cones, polar cones, convexity, Fenchel transform, subdifferentials, Fenchel-Young inequality were developed bottom-up. Loads of excerises with varying difficulty were provided to help the readers understanding of the material. Even though we worked in Banach spaces, most of the material presented there would still stand if we striped of the Banach space structure, and simply considered normed vector spaces (or just vector spaces in certain cases). This is what will be done here.

I.2 – Cones, sublinear functionals, seminorms, $K$-positivity

Let $\X$ be a real vector space with topological dual $\Xstar$ (i.e space of all linear functionals $\X \rightarrow \mathbb R$), and $V \subseteq \X$ be a subspace. An extension of a linear functional $\vstar \in V^\star$ is a linear functional $\xstar \in \Xstar$ such that $\xstar|_V = \vstar$, i.e $\xstar(v) = \vstar(v)$ for all $v \in V$.

A linear functional $\xstar \in \Xstar$ is called $K$-positive if $\xstar(x) \ge 0$ for all $x\in K$. The set of all $K$-positive $\xstar \in \Xstar$, denoted $\Kplus$, is called the dual cone of $K$. Similarly, the polar cone of $K$ is the subset $K^\circ := -\Kplus$ of all $K$-negative linear functionals $\xstar: \X: \rightarrow \mathbb R$. If $V$ is a subspace of $\X$, then $\Kplus|_{V}:=(K\cap V)^+ \cap V^\star$ is the space of $(K\cap V)$-positive linear functionals $v^\star \in V^\star$, i.e all linear functionals $v^\star:V \rightarrow \mathbb R$ such that $\vstar(v) \ge 0$ for all $v \in K\cap V$. Similarly, $K^\circ|_V := (K\cap V)^\circ \cap V^\star=-\Kplus|_F$ is the subset of all $(K\cap V)$-negative linear functionals $\vstar: V \rightarrow \mathbb R$. It is easy to check that $K^\circ$ are convex cones in $\Xstar$, while $K^+|_F$ and $K^\circ|_F$ are convex cones of $F^\star$.

Given a (nonempty) subset $C$ of $\X$, $C$ is said to be balanced if $\alpha C \subseteq C$ for all $\alpha \in [-1, 1]$. $C$ is said to be a cone if $\alpha C \subseteq C$ for all $\alpha \ge 0$. The Minkowski gauge of $C$ is the mapping $\rho_C:\X \rightarrow \mathbb R^+$ defined by

\[\rho_C(x) := \inf\;\{t > 0 \mid x \in tC\}.\]A function $\phi:\X \rightarrow \mathbb R$ is called sublinear if

- Positive-homogeneous: $\phi(\lambda x) = \lambda \phi(x),\;\forall (x,\lambda) \in \X \times \mathbb R^+$

- Subadditive: $\phi(x + x’) \le \phi(x) + \phi(x’),\;\forall (x,x’) \in \X \times \X$.

If $\phi:\X \rightarrow \mathbb R$ is a sublinear function which is symmetric about the origin, i.e $\phi(-x) = \phi(x),\;\forall x \in \X$, then we say $\phi$ is a seminorm on $\X$.

Lemma 2.1.2. The epigraph of every sublinear function $\phi: \X \rightarrow (-\infty,+\infty]$ is a convex cone of $\X \times \mathbb R$. In particular, every sublinear function is convex.

Proof. Let \(K := \{(x,\lambda) \mid \phi(x) \le \lambda \} \subseteq \X \times \mathbb R\) the epigraph of $\phi$. Let $z:=(x,\lambda), z’:=(x’,\lambda’) \in K$ and $\alpha,\alpha’ \ge 0$. Then by the sublinearity of $g$, we have

\[\phi(\alpha x + \alpha' x') \le \alpha \phi(x) + \alpha' \phi(x') \le \alpha\lambda + \alpha'\lambda',\]and so $\alpha z + \alpha’ z’ = (\alpha x + \alpha’ x’, \alpha\lambda + \alpha’\lambda’ ) \in K$. Thus $K$ is a convex cone and we are done. $\qed$.

I.3 – Exercises

Exercise 1.3.1. Let $u:\X \rightarrow \mathbb R$ be a function and $V_1$ be a nonempty subset of $\X$.

- Prove that $\sup_{v \in V_1}u(v) > -\infty$ and $\inf_{v \in V_1}u(v) < +\infty$.

- If $V_2$ is another subset of $\X$ such that $\sup_{v \in V_1}u(v) \le \inf_{v \in V_2}u(v’)$, prove that there exists $a \in \mathbb R$ such that $u(v) \le a \le u(v’)$ for all $(v,v’) \in V_1 \times V_2$.

Exercise 1.3.2. Show that for every linear functional $\xstar \in \Xstar$, the function $x \mapsto |\xstar(x)|$ is a seminorm on $\X$. (Hint. Use definition.)

Exercise 1.3.3. Show that if $C \subseteq \X$ is convex, then its Minkowski gauge $\rho_C$ is sublinear. Hint. Use definition.

Exercise 1.3.4. Show if $\phi:\X \rightarrow (-\infty, +\infty]$ is a seminorm, then $\phi(x) \ge 0 = \phi(0)$. (Hint. Use the fact that $2\phi(x) = \phi(x) + \phi(-x)$.)

Exercise 1.3.5. Let $\X$ be a real normed vector space and $\xstar \in \Xstar$ be a linear functional. Prove that the following are equivalent:

- $\xstar$ is continuous around the origin.

- $\xstar$ is bounded around the origin.

- $\xstar$ is continuous on the origin.

- $\xstar$ is bounded on $\X$.

Hint. Directly use the definitions of boundedness (at a origin) and continuity (at the origin).

Exercise 1.3.6. Let $C$ and $D$ be convex subsets of a real vector space $\X$ and let $\alpha,\beta \in \mathbb R$. Prove that the set \(\alpha C + \beta D := \{\alpha c + \beta d \mid (c,d) \in C \times D\}\) is a convex subset of $\X$.

Hint. $t (\alpha c + \beta d) + (1-t) (\alpha c’ + \beta d’) = \alpha(tc + (1-t)c’) + \beta (td + (1-t)d)$.

Exercise 1.3.7. Prove that $\phi:\X \rightarrow \mathbb R$ is a seminorm iff it is subadditive and satisfies $\phi(\lambda x) = |\lambda|\phi(x)$ for all $(x,\lambda) \in \X \times \mathbb R$. For $x \in \X$, let \(\dist(x, C) := \inf_{x \in C}\|x-x_0\|\) be the distance of the point $x$ from the set $C$.

Exericse 1.3.8. Let $C$ be a nonempty convex set of a real normed vector space $\X$.

- (A) Prove that for every bounded linear operator $\xstar \in \Xstar$, it holds that

- (B) Moreover, prove that if $C$ is convex, then \(\sup_{\xstar \in \BXstar}\inf_{x \in C}\xstar(x) = \dist(0, C),\) where $\BXstar$ is the unit ball of $\Xstar$.

Hint. Exercise 1.2.1 of previous post and Danskin-Bertsekas theorem (also from previous post).

II – Extension and separation theorems

The following Riez Extension Theorem is perhaps the most important result in all of convex geometry. It is a generalization of Helly’s Theorem and of the Hahn-Banach Theorems, which is the main ingredient in proving the FRDT.

Theorem 2.1 (Riez Extension Theorem). Let $\mathcal X$ be a real vector space and $V$ be a subspace of $\X$ and $K$ be a cone in $\X$ such that for every $x \in \X$ there exists $v,v’ \in V$ such that $x-v \in K$ and $x+v’ \in K$ (for example, this is the case if $\X=V+K$). Suppose either the quotient $\X/V$ is finite-dimensional or the Axiom of Choice is true. Then every $(K\cap V)$-positive linear functional $v^\star: V \rightarrow \mathbb R$ can be extended to a $K$-positive linear functional $\xstar: \X \rightarrow \mathbb R$.

Proof. The proof is by transfinite induction on the dimension of the quotient space $\X/V$. We prove the case $\dim \X/V = 1$, so that it sufficies to consider $\X=V \oplus \mathbb Rx_0 \cong V \times \mathbb R$, for some $x_0 \in \X$. Fix $a \in \mathbb R$. Now, given a linear functional $\vstar \in V^\star$, the linear functional $\xstar_a \in \Xstar$ defined by $\xstar_a(v + \lambda x_0) = \vstar(v) + \lambda a$ for all $(v,\lambda) \in V \times \mathbb R$ is a linear extension of $\vstar$. It remains to show that $\xstar_a$ is $K$-positive for some choice of $a \in \mathbb R$. This translates to the inequality

\[\begin{split} \exists a \in \mathbb R &\st \xstar(v + \lambda x_0) = \vstar(v) + \lambda a = \lambda(\vstar(v/\lambda) + a) \ge 0,\\ &\forall (v,\lambda) \in V \times \mathbb R \st v + \lambda x_0 \in K\cap V\; ? \end{split}\]which can be split into two inequalities depending on the sign of $\lambda$, viz

\[\exists a \in \mathbb \st \vstar(v) \le a\;\forall v \in (x_0-K)\cap V,\; \vstar(v) \ge a\;\forall v \in (x_0+K)\cap V \;? \tag{1}\]Now, let $v,v’ \in V \st x_0 - v, x_0 + v’ \in K$. Then $v’-v = x_0-v + x_0 + v’ \in K\cap V$ since $K$ is a convex cone and $V$ is a subspace of $\X$. Thus, since $\vstar: V \rightarrow \mathbb R$ is a $(K\cap V)$-positive linear functional, it follows that $\vstar(v’-v) \ge 0$, i.e $\vstar(v) \le \vstar(v’)$. Thus

\[-\infty < \sup_{v \in (x_0-K) \cap V}\vstar(v) \le \inf_{v' \in (x_0+K) \cap V}\vstar(v') < +\infty, \tag{2}\]where the first and last strict inequalities are because neither intersection is empty since by hypothesis, there exists $v, v’ \in V$ such that $x_0-v,x_0+v’ \in K$. But (2) implies (by Exercise 1.3.1), and we are done. $\qed$

II.1 – Hahn-Banach theorems

The following is a celebrated corollary to the Riesz extension theorem (Theorem 2.1 above).

Theorem 2.1.1 (Hahn-Banach Theorem, analytic version). Let $\X$ be a real vector space $\phi:\X \rightarrow (-\infty,+\infty]$ be a sublinear function. Let $V$ be a subspace of $\X$ and $\vstar: V \rightarrow \mathbb R$ a linear functional such that $\vstar(v) \le \phi(v)\;\forall v \in V$. Suppose either he quotient $\X/V$ is finite-dimensional or the Axiom of Choice is true. Then $\vstar$ can be extended to a linear functional $\xstar:\Xstar \rightarrow \mathbb R$ such that $\xstar(x) \le \phi(x)\;\forall x \in \X$.

Proof. Let \(K := \{(x,\lambda) \mid \phi(x) \le \lambda\} \subseteq \X \times \mathbb R\) be the epigraph of $\phi$. By Lemma 2.2.1, $K$ is a convex cone of $\X \times \mathbb R$. Now consider the linear functional $\ustar: V \times \mathbb R \rightarrow \mathbb R$ defined by $\ustar((v, \lambda)) := \lambda - \vstar(v)$. Thus for every $(v,\lambda) \in K \cap (V \times \mathbb R)$, one has

\[\ustar((v, \lambda)) = \lambda - \vstar(v) \ge \lambda - \phi(v) \ge 0,\]where the inequality is by hypothesis and the fact that $v \in V$, and the second inequality by definition of $K$ and the fact that $(v,\lambda) \in K$. Thus $\ustar$ is a $(K \cap (V \times \mathbb R))$-positive linear functional on $V \times \mathbb R$. Thus, by Theorem 2.1, $\ustar$ can be extended to a $(V \times \mathbb R)$-positive linear functional $\zstar$ on $\X \times \mathbb R$.

We now show that the linear functional $\xstar:\X \rightarrow \mathbb R$ defined by $\xstar(x) := -\zstar(x, 0)$ is the desired linear extension. Indeed, if $x \in \X$ with $\xstar(x) > \phi(x)$, then

\[\zstar(x,\phi(x)) = \phi(x) + \zstar(x,0)=\phi(x)-\xstar(x) < 0,\]whereas $(x,\phi(x)) \in K$ (because $\phi(x) \le \phi(x)$, obviously!), a contradiction the fact that $\zstar$ is a $(V \times \mathbb R)$-positive linear functional on $\X$. $\qed$

Definition (separating hyperplane). A separating hyperplane for (disjoint) subsets $C$ and $D$ of a real vector space is a pair $(\xstar,\alpha)$ where $\alpha \in \mathbb R$ and $\xstar$ is a continuous nonzero linear functional on $\X$, such that $\xstar(c) \le \alpha \le \xstar(d)$ for all $(c,d) \in C \times D$.

Lemma 2.1.2 (Hahn-Banach Separation Theorem, geometric version for a point). Let $\X$ be a real normed vector space and $C$ be a convex subset of $\X$ with nonempty interior, and $x_0 \in \X\setminus C$. Then there exists a separating hyperplane between $x_0$ and $D$.

Proof. Let \(V = \mathbb Rx_0 := \{\lambda x_0 \mid \lambda \in \mathbb R\}\), a one-dimenional subspace of $\X$, and define the linear functional $\vstar: V \rightarrow \mathbb R$ by $\vstar(\lambda x_0) = \lambda$ for all $\lambda \in \mathbb R$. Because $x_0 \not\in C$ by hypothesis, it holds that $\lambda x_0 \not\in \lambda C$ for all \(\lambda \in \mathbb R\setminus\{0\}\), and so $\rho_C(\lambda x_0) \ge \lambda := \vstar(\lambda x_0)$ for all $\lambda \in \mathbb R$, i.e $\vstar(x) \le \rho_C(x)$ for all $x \in V$. Thus since $\rho_C$ is sublinear, by the Hahn-Banach Separation Theorem, there exists a linear functional $\xstar:\X \rightarrow \mathbb R$ such that $\xstar|_V = \vstar$ and $\xstar(x) \le \rho_C(x)$ for all $x \in \X$. Thus for all $x \in C$, one has $\xstar(x) \le \rho_C(x) = 1 = \xstar(x_0)$.

It remains to show that $\xstar$ is continuous. By Exercise 1.1.4, it suffices to show that it is continuous around the origin $0$. Since $C$ has nonempty interior, without loss of generality, suppose $0 \in \inte(C)$; otherwise just translate $C$. Let $\varepsilon > 0$, and $x \in \X$ with \(\|x\|\) sufficiently small so that $\pm x/\varepsilon \in C$. This is possible becase $0$ is an iterior point of $C$. Then by linearity of $\xstar$, we have $(1/\varepsilon)\xstar(x)=\xstar(x/\varepsilon) \le 1$ and $-(1/\varepsilon)\xstar(x)=\xstar(-x/\varepsilon) \le 1$. Thus $|\xstar(x)| \le \varepsilon$, and so $\xstar$ is continuous around the origin. $\qed$

The following is the geometric version of Theorem 2.2, and an essential ingredient for proving the FRDT. Viz

Theorem 2.1.3 (Hahn-Banach Separation Theorem, geometric version). Let $\X$ be a real vector space and $C_1$ and $C_2$ disjoint convex sets such that $C_1$ has nonempty interior. Then there exists a separating hyperplane between $C_1$ and $C_2$.

Proof. Consider the set \(C := C_2 - C_1 := \{d - c \mid (c_1,c_2) \in C_1 \times C_2\}\). Then $C$ is a convex subset of $\X$ (Exercise 1.3.6) not containing the origin $0$ (since $C_1 \cap C_2 = \emptyset$). Also, since $C_1$ has nonempty interior, so does $C$. Thus we can apply Lemma 2.1.2 with $x_0 = 0$, to get that there exists a separating hyperplane $(\xstar,\alpha)$ between $0$ and $C$. Spelling things out, this means

\[\xstar(x) \le \alpha \le \xstar(0) = 0,\;\forall x \in C.\]In particular, since $c_2-c_1$ is an element of $C$ for every $(c_1,c_2) \in C_1 \times C_2$, it follows that $\xstar(c_2) - \xstar(c_1) = \xstar(c_2 - c_1) \le 0$. Thus

\[\sup_{c_2 \in C_2} \xstar(c_2) \le \inf_{c_1 \in C_1}\xstar(c_1).\]By continuity of $\xstar$, it’s range $\xstar(\X)$ is a subset of $\mathbb R$ and so by Exercise 1.3.1, there exists $\alpha \in \mathbb R$ such that $\xstar(c_2) \le \alpha \le \xstar(c_1)$ for all $(c_1,c_2) \in C_1 \times C_2$, and we are done. $\qed$

II – Conclusion

We are now in good shape to emback on a proof of the FRDT. This will be done in the next (and final) post. To be continued…

References

- The Hahn-Banach separation Theorem and other separation results”, by Robert Peng

- Théorème de prolongement de M. Riesz, by wikipedia.org